How To Change Code On Chamberlain Garage Door Opener

Policy —

What is DRM doing in my garage?

My new garage door opener comes with both DRM and a DMCA warning: don't even …

I never expected to stumble upon a Digital Millennium Copyright Deed (DMCA) story while standing below an unshielded light bulb in my garage, but that was before I picked upwards the transmission for my garage door opener.

I recently moved houses, and during a Saturday largely spent immigration a terrific mass from my new garage, I came across a tattered copy of the owner's manual for the garage door opener, thoughtfully left behind for my use. I read through the manual looking for information on how to acquire another remote control unit of measurement, when my eye was caught past the sort of statement one does not expect to find in any sort of literature relating to the apprehensive garage door.

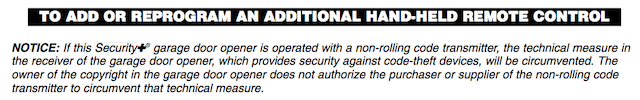

"If this Security+ garage door opener is operated with a non-rolling code transmitter, the technical measure out in the receiver of the garage door opener, which provides security confronting code-theft devices, volition be circumvented," said the manual. "The possessor of the copyright in the garage door opener does not authorize the purchaser or supplier of the non-rolling code transmitter to circumvent that technical mensurate."

The find, in all its celebrity

Bizarre. Though the words "Digital Millennium Copyright Act" were never mentioned, the law's anticircumvention provisions were clearly existence referenced here. Only those provisions were designed to brand breaking the digital rights direction (DRM) on DVDs, music downloads, and computer games illegal—and past doing and so would help keep DRM-busting devices off of the market. What was this nonsense virtually circumventing technical measures doing in my garage door opener transmission, and why did the transmission become out of its style to go far articulate that I was not "authorized" to apply a specific sort of remote control?

"Code grabbers," DRM, and the garage door

The picture became a little clearer when I flipped back to the front page; the opener was made past Chamberlain, the largest garage door opener company in the US.

Those who take followed tech law for some time volition remember that Chamberlain was at the center of a seminal DMCA instance back in 2003-2004. Chamberlain sued a Canadian company called Skylink, which made universal garage door openers, on the grounds that Skylink'due south devices were bypassing a DRM scheme and that Skylink was therefore "trafficking" in circumvention devices under the DMCA.

DRM, what hath yous wrought?

For years, garage door remote controls were simple devices that beamed an RF signal at a garage door, which then opened. The setup was insecure, even when each remote and opener unit of measurement used an unchanging but unique shared central (a "non-rolling lawmaking") to authenticate the "open" command. As the federal appeals court noted in its write-up of the case, "According to Chamberlain, the typical GDO is vulnerable to attack by burglars who tin can open up the garage door using a 'lawmaking grabber.' Chamberlain says that code grabbers allow burglars in close proximity to a homeowner operating her garage door to record the bespeak sent from the transmitter to the opener, and to return later, replay the recorded signal, and open up the garage door."

"Code grabbing" appears to be something of an urban myth, however; the court went on to say that "Chamberlain concedes, nevertheless, that lawmaking grabbers are more theoretical than applied burgling devices; none of its witnesses had either immediate cognition of a unmarried code grabbing problem or familiarity with data demonstrating the being of a problem. Nevertheless, Chamberlain claims to have developed its rolling code arrangement specifically to forbid code grabbing." A footnote reveals that competitor Skylink offered a snarkier caption for Chamberlain's move to a "rolling code" system: Chamberlain'due south openers suffered from "inadvertent GDO [garage door opener] activation by planes passing overhead, not as a security measure."

("Oh, snap!" as they say in the legal world.)

Chamberlain's new, secure, definitely-non-triggered-by-low-flying-aircraft innovation was the rolling code. New "Security+" transmitters would broadcast a two-part signal containing a device identification code (fixed) and then a security code (changing). Every time the garage door opens, the opener and the remote agree to change the security code, and they have a few billion choices to pick from. A "code grabber" who rolled up to the house and attempted to open the garage using a recorded signal would find himself locked out.

Straightforward stuff—but how did Skylink bypass it? The company didn't make a rolling code transmitter, instead relying on a bit of trickery. The Skylink universal remote opens Chamberlain garage doors by sending out the correct device identification code and so three signals, none of which accept any connectedness to the expected security code. The starting time bespeak, because it is incorrect, is ignored past the opener. The second point is too an incorrect code, but coming so close to the beginning, information technology triggers to opener to look for a 3rd security code to follow milliseconds later, 1 which differs from the second code past a value of three. If this happens, the opener triggers its ain "resynchronization" sequence, resets the code windows it has been using, and (crucially) opens the garage door.

It was a cracking bit of trickery, simply Chamberlain argued that it violated section 1201(a) of the Copyright Act, the department against circumventing technical protection measures. Skylink claimed numerous defenses, including the fact that information technology was protected by 1201(f) on reverse technology. In addition, Skylink argued that the rolling code was not DRM, since information technology did not protect admission to some copyrighted computer lawmaking but to "an uncopyrightable process" (the opening of a garage door).

Making criminals of customers

The case went badly for Chamberlain, both at the federal courthouse here in Chicago and so when the Court of Appeals took up the case in 2004. Both times, some of the highest judges in the country found the argument preposterous; if true, non just would a third-political party competitor who made garage door openers be guilty of trafficking in illicit devices, but every homeowner who used a Skylink remote would themselves have violated the DMCA's anticircumvention rules.

Both federal courts that looked at the case "declined to adopt a construction with such dire implications." In other words, they refused to say that hundreds of thousands of garage-door owning Americans were breaking federal law by purchasing cheap replacement remotes. (One wonders whether this logic would be extended to ripping a DVD onto a laptop just earlier a flight; the exact same consequences follow.)

But across this reductio advertising absurdum, the courts also found a more technical reason for tossing Chamberlain's case: the company had never proved that "the circumvention of its technological measures enabled unauthorized access to its copyrighted software," with the central word being "unauthorized." If Chamberlain had only made articulate in advance that certain uses were unauthorized, who knows? It might have prevailed.

Equally the appeals court noted when reviewing the lower court's conclusion, "The Commune Court agreed that Chamberlain'southward unconditioned sale implied authorization... Chamberlain places no explicit restrictions on the types of transmitter that the homeowner may use with its system at the fourth dimension of purchase. Chamberlain's customers therefore assume that they enjoy all of the rights associated with the use of their GDOs and any software embedded therein that the copyright laws and other laws of commerce provide."

The lawyers speak

So—a 2004 two-courtroom judicial smackdown, consummate with summary judgment in favor of Skylink. The issue wasn't even a close call. And then why was I standing in my garage on a absurd Nov Sabbatum, staring down at text telling me I could not employ non-rolling code transmitters? I checked the appointment on the manual; it was from 2006, and other recent manuals on Chamberlain's website comprise the same statement.

I checked in with several lawyers who had participated in the Chamberlain/Skylink case. Matt Schruers filed an amicus cursory in the case on behalf of computer industry trade group CCIA, which argued that the DMCA could non be used merely to prevent competition. When I asked Schruers what he made of the notice, he was intrigued.

"I keep seeing the Chamberlain door openers in the Costco and I've wondered what they were upwardly to these days," he said. Equally for the notice, he said it looked like "an effort to write around the conclusion that the Federal Excursion reached" by clearly refusing authorization to use Skylink's non-rolling code universal remote.

Seth Greenstein, who litigated a like case involving Lexmark toner and ink cartridges (encounter below), agreed that the notice in my transmission was an attempt to bypass a role of the court'south logic. "The element relevant to your question is that the access enabled by the circumvention must exist unauthorized," he said. "The court institute the unrestricted sale of the GDO implicitly authorized the purchaser to employ the opener, including the right to acquire replacement controls. The new text ostensibly remedies that prior omission."

But Schruers didn't retrieve the text was probable to stand up upwards in courtroom. "The revocation of authorization would, at a minimum, need to be part of an explicit contract betwixt the buyer and seller," he pointed out, which appears to be lacking here.

"All that being said," he added, "naught seems to prevent Chamberlain from attempting to prohibit sure acquit in their documentation, even if the prohibition is unenforceable. By way of example, DVDs marked 'for abode use' or 'non-commercial private use merely' are not legally restricted as such. Unless there is a contract, those representations are non true. A given use, e.thou., classroom showing, is permitted or infringing depending on copyright police, non what is printed on the packaging—unless there is a contract including that restriction. Rightsholders still print such claims on the packaging, however. They might too impress that infringers are obligated to forfeit their first-born child."

Jonathan Band, a DC lawyer who also worked on the CCIA brief and is now in private practice, noted that Chamberlain also had to overcome a 2d hurdle. "While the case was on entreatment," he said, "Chamberlain added the linguistic communication that you lot saw in an effort to argue with respect to new openers that there was no authorization. [Just] the Federal Circuit decided the case on other grounds, i.e., that in that location was no nexus betwixt the circumvention and infringement. Thus, the Chamberlain language does not bear upon the Federal Circuit's rationale."

I went dorsum to the appeals court decision and found the department that Band was referencing. While the court did speak extensively almost "say-so," information technology also fabricated the following crucial point: "The essence of the DMCA's anticircumvention provisions is that sections1201(a),(b) establish causes of action for liability. They do not plant a new property right. The DMCA's text indicates that circumvention is non infringement."

Translated into English, the court is saying that DMCA anticircumvention rules merely provide new liability for accessing copyrighted material without authority, only that circumvention itself was not a copyright violation. Since Skylink's remote did not make copies of Chamberlain code and did not provide access to that lawmaking, the necessary "nexus" betwixt bypassing the DRM and infringing on Chamberlain copyrights was missing.

We contacted Chamberlain to get their side of the story but received no response.

Source: https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2009/12/what-is-drm-doing-in-my-garage/

Posted by: dennisalannow.blogspot.com

I think this is an informative post and it is very useful and knowledgeable. therefore, I would like to thank you for the efforts you have made in writing this article. garage door repair

ReplyDelete